Adventures in Kākāpō Land

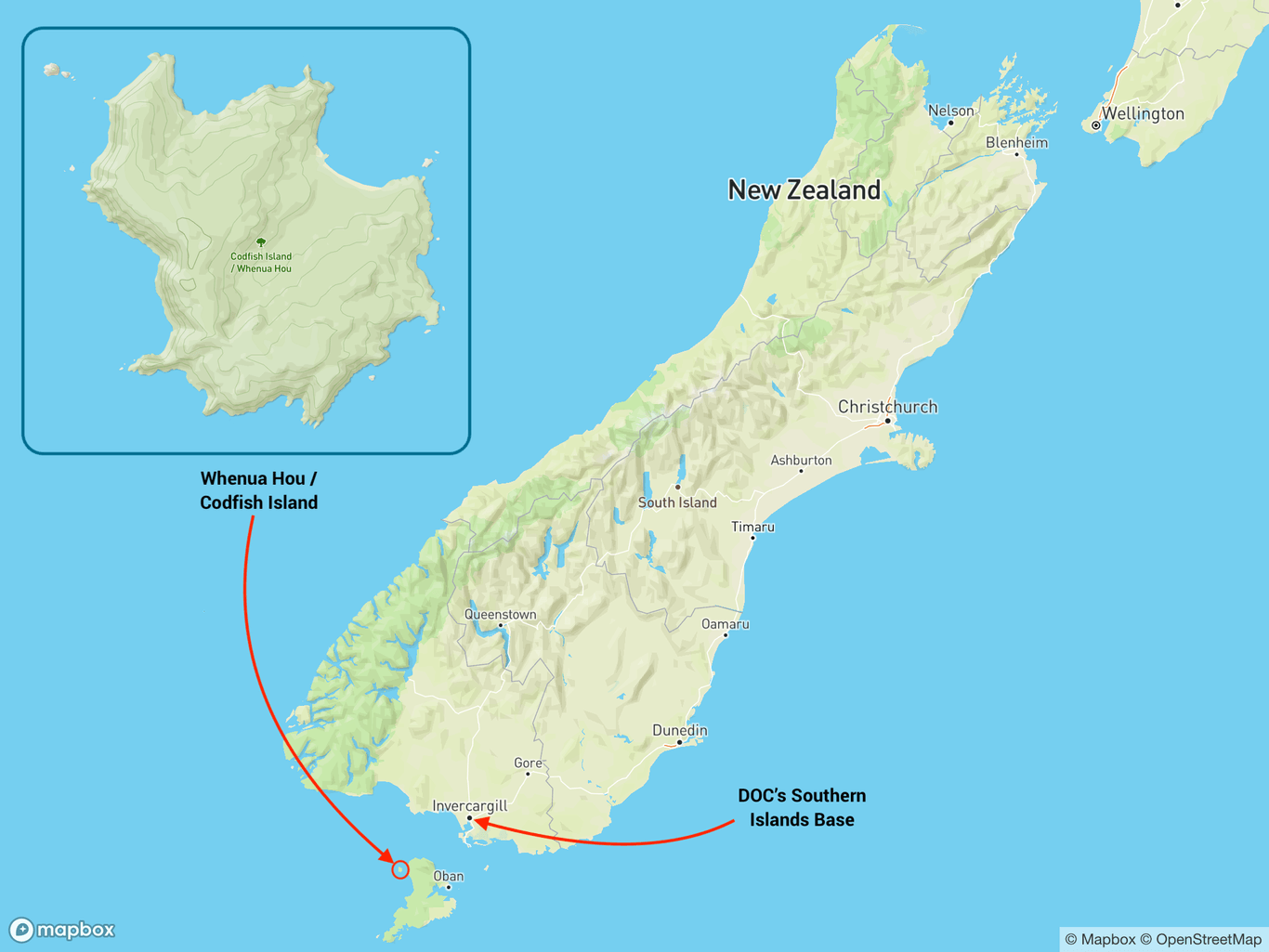

Recently I was lucky to spend two weeks on Whenua Hou/Codfish Island, a forest-covered predator free nature reserve next to Rakiura/Stewart Island. About 14km^2 in size, with a high point of 250m, it is a known wildlife hotspot and also of great cultural significance to Ngāi Tahu, with human connections interwoven in the history of the place.

The reason for my visit was to help out the Kākāpō Recovery programme, which has been based there since 1987. Kākāpō are a critically-endangered endemic, nocturnal, flightless parrot, and there are only 201 individuals left in the world (as of the time of writing). All kākāpō currently live on off-shore predator free islands, as introduced mammalian predators would otherwise wipe them out.

Looking towards the Ruggedy Mountains from a high point on Whenua Hou

Looking towards the Ruggedy Mountains from a high point on Whenua Hou

They are weird birds, particularly when compared with other parrots as they are1:

- nocturnal

- flightless

- lek-breeding (males make booming noises to attact females to a specific location)

- long-lived (estimated to live up to 90 years)

- the heaviest parrot in the world (can be 4kg or more)

One kākāpō, Sirocco, is the national spokesbird for conservation, becoming famous for attempting to mate with a zoologist’s head while filming a BBC documentary.

A kākāpō! This one is named Morehu, a 22-year-old adult male.

A kākāpō! This one is named Morehu, a 22-year-old adult male.

How did I end up here?

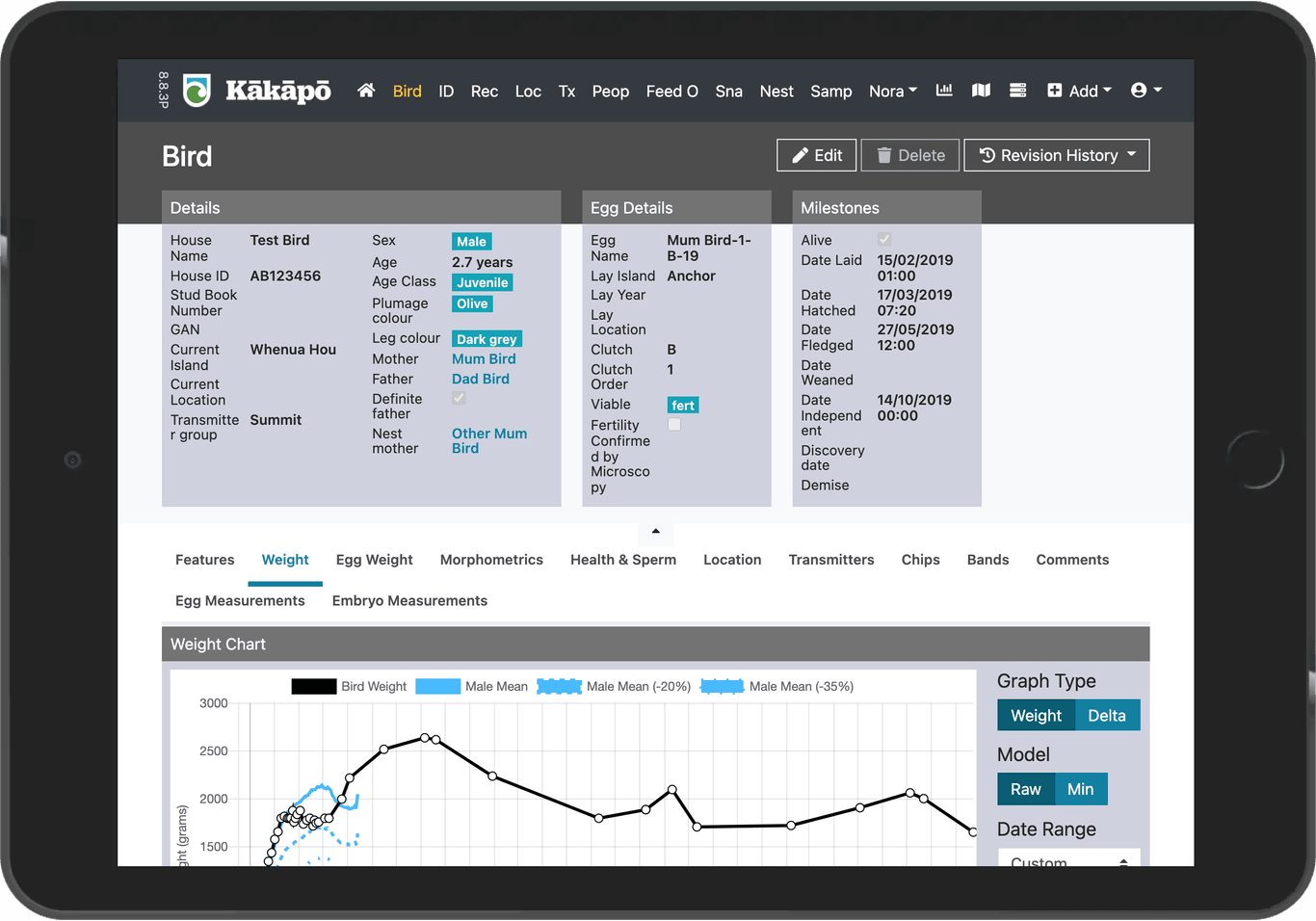

After deciding to take a gap year from my studies in France, I landed a fixed-term developer job at the Department of Conservation (DOC) | Te Papa Atawhai. I spent much of the year working on Dusky, the kākāpō database. Unlike most other bird databases, Dusky contains information on every single individual. As such, the database captures large amounts of different data including bird details, egg/chick weights, transmitter changes, supplementary feeding, biological samples/results, and information received from ‘NoraNet’, a long distance network on the islands receiving information from bird transmitters and other devices.

Dusky was also recently released as open source code, meaning anyone can use and modify the source code.

After asking earlier in the year if I could maybe be somewhat useful in the field, I got the go-ahead to do a two week stint on one of the islands, in the lead-up period to the predicted breeding season (kākāpō only breed every few years). Soon enough, I found myself on a flight to Invercargill/Waihōpai where DOC’s Southern Islands operations are based. Spending a day working from the local office, I was quickly put to work helping screw together some batteries and cables, ready to be transported to the islands for use with radio devices called ‘snarks’.

The next day, we headed to the quarantine facility (“Q-Store”), where our previously disinfected clothing/gear was double-checked to make sure we didn’t accidentally transport any unwanted pests, weeds or diseases to the island. A couple hours later, we were driven to Bluff/Motupōhue and loaded onto a helicopter for a short flight over Foveaux Strait/Te Ara a Kiwa. Landing on a patch of grass just above the beach, we formed a human chain to quickly unload and reload people and boxes. It wasn’t long until the helicopter was taking off again, the whuppa-whuppa sound retreating to reveal the sounds of waves breaking on the sand nearby.

Key locations, relative to the South Island/Te Waipounamu

Key locations, relative to the South Island/Te Waipounamu

Island life

After transporting the various bags, boxes and bits to the “Sealers Bay Resort & Spa”, we were soon taken around for our health & safety induction. We were subsequently left to our own devices for the arvo, as the rangers did some planning. With me on the island were three kākāpō rangers: Jake, Bryony and Sarah, alongside three feed-out volunteers: Coralie, Josh & Donavin. The feed-out volunteers’ role was to help with the supplementary feeding, to help make sure the birds were at an ideal weight for the breeding season.

My main role was to help out Jake, the technology ranger, with various tasks related to NoraNet. NoraNet is the name for a network of radio devices known as ‘snarks’ located across the island, which enable the kākāpō team to automatically receive information about things such as bird activity and whether mating or nesting activity has been recorded. Some snarks are also attached to scales and ‘smart hoppers’, which enable the automatic collection of bird weight data and permitting/excluding certain birds from accessing the hoppers containing food.

Over the next 14 days I was variously involved in:

- Updating firmware on ‘Errol’, ‘Hub’ and ‘Relay’ snarks, strategically located at north-facing high points around the island

- Reviewing trail camera footage

- Transporting scales around (each about 2kg in weight)

- The occasional meeting with head office

- Data entry into Dusky

- Unloading/reloading flights

- Heading out to go find kākāpō (more on that later)

Daily hut life has everyone contributing to cooking dinners, doing dishes and various other chores. The hut itself has all the mod-cons, including power, hot water and fridges/freezers. The water out of most of the taps runs brown due to its origins in the nearby tannin-stained creek. Although slightly weird at first, it does have the amusing side effect of making it seem like people are drinking (flat) beer at all times. I also remember one evening trying to sleep but was being kept awake by the sounds of native penguins, seabirds and the ‘skraaks’ of nearby kākāpō—had to remind myself I was fortunate to have my sleep disrupted by these sounds!

A ‘Super Errol’ receiving device (part of NoraNet), and a ‘smart hopper’ feeding station with a set of scales

A ‘Super Errol’ receiving device (part of NoraNet), and a ‘smart hopper’ feeding station with a set of scales

Helping to unload one of the supply flights

Helping to unload one of the supply flights

Finding the kākāpō

Partway through my trip, a bunch of other friendly kākāpō rangers joined us for a few days, with a mission of fitting GPS trackers to some kākāpō as part of a study. Each day we split up into 3 to 4 different ‘catch teams’, and scattered across the island to try and find these birds.

Armed with the trusty ‘TR4’ receivers, we used directional antennae to listen for ‘blips’ being sent out by transmitters. Essentially the way it works is you rotate the antenna and listen to the blips, trying to find the direction in which the blips are strongest. In theory, you then head in this direction, and/or do some triangulation, and you will eventually find a bird. Naturally, the reality is a tad more complicated than that, with blips sometimes seeming to come from opposing directions, and the signals being bounced around by geographical features. There’s a certain amount of intuition and luck involved!

![]() Getting an idea of where the target birds are (Photo: Andrew Digby)

Getting an idea of where the target birds are (Photo: Andrew Digby)

Despite there being tracks on the island, they will only get you so far. Most of the time spent trying to find a kākāpō is off-track in native forest and/or scrub. Sometimes you strike it lucky, and you find the kākāpō in a reasonably open patch of forest, not too far from the track. Other times you end up getting tangled up in supplejack vines or have to bash through ‘muttonbird scrub’ full of wood that’s solid enough to scratch you as you walk past, but weak enough that it won’t support your weight as you’re trying to clamber up or down a steep hillside following a kākāpō that’s on the move.

Having fun in a patch of vines

Having fun in a patch of vines

When we do eventually locate a kākāpō, it’s not uncommon to find them roosting high up a tree. Despite being flightless, they are very impressive climbers, getting around the forest canopy as deftly as flying birds half their weight. If they’re low enough, we can often get them from the tree, but if they’re too high then we have to abandon our mission.

Sometimes things do actually go to plan and we manage to catch one of the birds. They are unceremoniously placed in a ‘catch bag’ while we get things ready. Once ready, the kākāpō is weighed then carefully removed from the bag. One person holds the bird, and the other one checks the transmitter harness, sticks on the GPS tracker, then performs a quick but thorough health check. Assuming all is well, the bird is released. Once let go, some birds run away while others stick around before clumsily scuttling into the undergrowth.

A successful mission; and a failed mission (spot the kākāpō tail feathers!)

A successful mission; and a failed mission (spot the kākāpō tail feathers!)

My role in these trips was to be a bird holder—given kākāpō are relatives of the kea (the bird I volunteer a lot of my time to help), the technique for holding them was fairly similar. Despite the ruffled apperance in the picture, the fingers of my right hand are placed on boney parts of the kākāpō’s head, and my left hand is securing the two legs. The weight of the bird is resting on my leg. We carefully keep an eye on the birds’ wellbeing as they’re being held, keeping an eye out for signs of any discomfort or stress.

The kākāpō I held seemed mostly quite relaxed, compared to some of the kea I’ve held that spent their time trying to bite and/or grab my fingers. Hopefully the Kākāpō Recovery programme becomes so successful in the long run that future kākāpō will never need to be handled by humans!

Final thoughts

It was super neat to be able to lend a hand with such a unique wildlife recovery programme. The skill, enthusiasm and dedication to conservation of the people I met is a credit to the team and the wider Department of Conservation. Here’s hoping for heaps of new healthy kākāpō chicks in the new year!

The crew: (L-R) Coralie, Donavin, Josh, Jake, Bryony, me, Sarah (Photo: Jen Waite)

The crew: (L-R) Coralie, Donavin, Josh, Jake, Bryony, me, Sarah (Photo: Jen Waite)