Citizen science for biodiversity monitoring in New Zealand

Citizen science, the collaborative collection of scientific data by the general public, is an increasingly relevant field in an age of modern technology. It presents an exciting opportunity, not only to collect new information that may have been not previously viable to obtain, but also to educate and engage people in science.

Last year as part of a third-year geography paper at the University of Canterbury, myself and four other students were tasked with helping the Christchurch-based community group Avon-Ōtākaro Network (AvON), whose aim is promote the future use of the Avon River/Ōtākaro and its surrounds as an ecological and recreational reserve for the community.

As part of this, one of AvON’s key undertakings is the Mahinga Kai Exemplar (MKE) project. In a nutshell mahinga kai is a Māori way of thinking that involves the simultaneous protection and use of food resources, and encompasses the wider social, cultural, educational and sustainable aspects of food. This includes the customs and ways that it is gathered, in line with kaitiaki (guardianship), whakapapa (geneology) and rangatiratanga (leadership).

In this case, the MKE project is referring to an ecological restoration project on the edges of Christchurch’s residential red zone (RRZ), either side of Anzac Drive in Burwood.

Part of the Mahinga Kai Exemplar site, situated either side of Anzac Drive in Christchurch.

Part of the Mahinga Kai Exemplar site, situated either side of Anzac Drive in Christchurch.

In order to judge the success of the ecological restoration aspect of the project, AvON wanted to determine the most viable option for monitoring biodiversity in the MKE area. Considering both the need to collect scientific information and also to engage and educate the local community, a citizen science approach looked to be the best fit for the project.

To figure out how AvON might do this, rather than reinvent the wheel our group decided to interview ten other New Zealand groups undertaking biodiversity monitoring to find out how they were doing it. Using the results of these interviews, combined with local and international literature, our group came up with six general recommendations for community groups undertaking citizen science projects in New Zealand.

The goal of these recommendations is to provide some practical considerations that community groups might wish to look at before conducting a citizen science project to help ensure its ongoing success.

Recommendations

Identify target or indicator species

Other biodiversity monitoring projects have been less successful in the past because of monitoring programmes that were too broad or unrealistic. As several initiatives recognised, monitoring changes in pest, bird, vegetation or fish taxa can all be effective approaches, but only if reliable and achievable sample sizes are used. Within the results, the identification of key species was identified as the most efficient method of managing the scope of a monitoring programme. However, main target species do not necessarily have to be native or threatened—monitoring pest and invasive species can be an excellent method for assessing changes over time.

For example, our observations at the MKE site demonstrated Canada Geese (Branta canadensis) were prominent in several locations. This nuisance species could be one that is targeted by monitoring, with controls put in place to regulate the population.

Using appropriate data collection methods to ensure community involvement

Most case studies noted the challenge of engaging the community with biodiversity monitoring, as certain aspects of data collection and analysis require extensive training and technical expertise. Training volunteers in more specialised areas of monitoring (e.g. invertebrate identification) was cited in several interviews as being too expensive and time consuming for existing staff, with many instead choosing to adopt multiple roles and work longer hours to ensure consistent data quality. This can alienate the public and volunteers as their contributions can be promoted as being less credible than those of senior staff.

Instead, it is important that accessible methods are used, such as bird counts, acoustic recordings, interaction via mobile apps and pest trapping. These approaches would cater for volunteers with varying experience without compromising the overall credibility of the data collected, and in many cases can be verified by scientific experts (e.g. cross-checking photographs).

Create a resilient framework for data management

One problem encountered by some of the groups surveyed was that the personnel involved in monitoring changed over time. This lead to varying and subjective data over the study period, as replacement staff used altered methods or approaches. Therefore, ensuring that there is clear guidance on how to gather and store data over time is critical for longevity and integrity. This might be achieved through the establishment of an online database with objectives, guidelines and feedback.

One piece of literature discussed the value of developing user-friendly online data entry systems, allowing individuals to maintain consistent data as well as other experts and organisations to provide ongoing feedback. This method also helps address the potential subjectivity of volunteers.

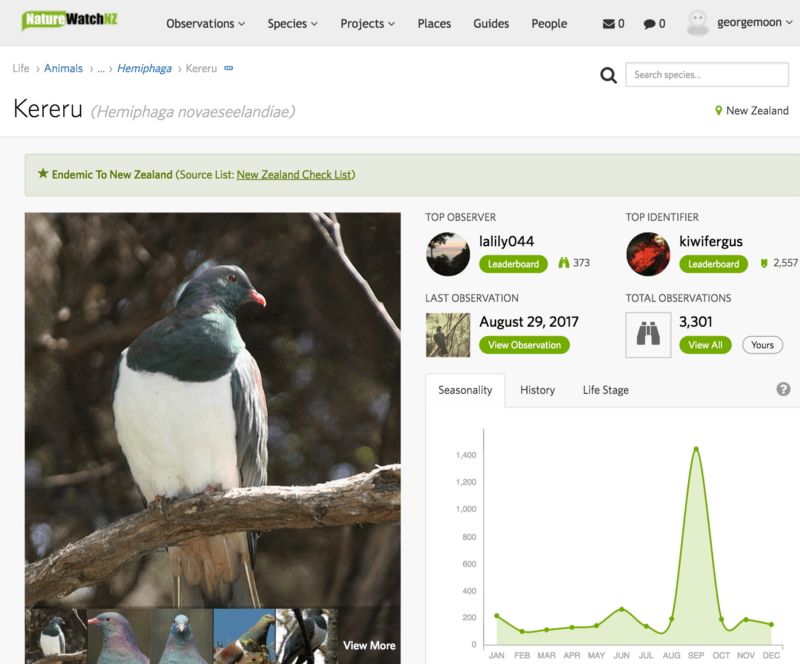

In New Zealand there are already many online databases, such as iNaturalist NZ, that would provide a suitable resilient data storage system. A decision to make an entirely separate database should not be taken lightly as it would then require continual updating and maintenance to ensure longevity and resiliency—if this is to be done, it is always better to use an established framework for database management, instead of designing something from the ground up.

iNaturalist NZ (formerly NatureWatch NZ), a citizen science website where people can record observations of species

iNaturalist NZ (formerly NatureWatch NZ), a citizen science website where people can record observations of species

Develop a monitoring/education pack

Another way to help remedy issues surrounding data consistency would be the creation of “biodiversity monitoring packs”, with information that ensures volunteers have the appropriate resources to collect and interpret quality data. Included within the packs could be information sheets, identification charts, links to download an app, learning tools and equipment specifically aimed at monitoring the target area. These could be designed for different age groups and distributed to local schools or other participating organisations allowing volunteers to have the relevant knowledge on-hand, either as part of an education programme or in their own time. The use of biodiversity monitoring packs linked with an online database was noted as being of especially high value by one of the groups interviewed.

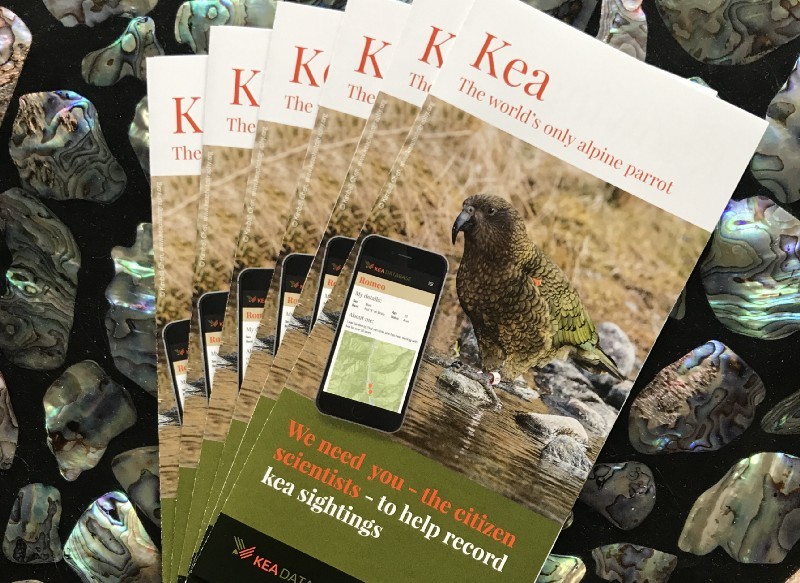

Some of the brochures used for the kea citizen science project

Some of the brochures used for the kea citizen science project

Create a volunteer rewards programme

Our research suggested that although there is currently a wide range of information available on how to monitor biodiversity, there are ongoing concerns with the limited numbers of volunteers involved with citizen science. This could be due to a lack of enthusiasm about volunteer programmes or issues with availability as a result of busy schedules.

One solution could be to develop a rewards initiative to engage and incentivise people. For example, as volunteers give their time and contribute to the project, they could be rewarded with points that may be used for discounts at local businesses willing to participate. An alternative option might be using a system similar to a ‘time bank’ in which volunteering hours generate ‘time credits’ that could be traded for different services.

Hopefully through engaging more people, it would result in more comprehensive spatial and temporal data within the area being monitored.

Establish a wider context

A big part of motivating volunteers is giving them the sense that all of their efforts are contributing to the ‘bigger picture’. It is important that they are provided with knowledge of the wider environmental, social and cultural ideas they are working towards, as it can also lead to a sense of stewardship & ownership of the project as well.

On this note, an article reviewed suggested that by reframing ecological sites as an ‘experience’ of aesthetic, educational and cultural significance for visitors, people are more likely to value them and exhibit stewardship.

The use of signage and displays throughout sites were promoted by several community groups as a good method to convey this sort of information—or alternatively it could be included in the ‘monitoring pack’ as discussed earlier.

One of the signs in the Mahinga Kai Exemplar area

One of the signs in the Mahinga Kai Exemplar area

Putting it into practice

An example of a citizen science project that takes into account many of these recommendations is the Kea Database.

- Identify target or indicator species

Obviously for a kea project, kea (Nestor notabilis) are the target species—easily identifiable and highly interactive! - Using appropriate data collection methods to ensure community involvement

The Kea Database uses a simple form that allows people to find their location on a map, then add the band combos of the birds they saw. They are also able to send photos for further verification, and are required to provide their email address so their sighting can be further clarified if necessary. - Create a resilient framework for data management

With other biodiversity citizen science platforms proving unsuitable for the maintenance of a database of individual birds (i.e. not just species level), a database was designed using well-established frameworks (PostGIS & Django) and interfaces (REST API). The code behind the database is also available online for anyone else wanting to undertake something similar. - Develop a monitoring/education pack

The kea project involves the printing of thousands of informative brochures so people know what to look for when recording sightings of kea. The goal is to get these brochures (along with complementary posters) out to all places where kea might be found—DOC huts, ski-fields, visitor centres etc. - Create a volunteer rewards programme

This is something that has not been pursued specifically, but because the project allows for the identification of individual bird we’re hoping that people will keep coming back to see how their favourite birds are getting on—especially with birds that are sponsored by community groups and businesses. - Establish a wider context

Often people don’t realise how endangered kea are, hence the brochures also have information about the threats facing kea. They also seek to explain why we are banding birds and collecting sightings information. Another major part of the project was the construction of the ‘Arthur’s Pass Kea Information Shelter’, a physical shelter with six large informational boards all about kea.

In summary

In summary, citizen science presents an exciting opportunity for biodiversity monitoring, both to collect scientific data and engage the wider public. In saying that, in order to undertake monitoring in this way, there are a number of steps that could help ensure the longevity and usefulness of the project.

Some of the recommendations might appear to be quite obvious, but the purpose of the research was to provide some academic substance to these, through both the review of literature and the examination of similar initiatives in New Zealand.

The literature reviewed suggested that the benefits are not limited to scientific outcomes—involving communities can help enhance social capital, educate, and engage with the concept of mātauranga (wisdom). It is for these reasons that citizen science should be seriously considered for any new community biodiversity monitoring projects.

Reference

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the other group members who contributed to the original report: Will Keay, Tim Stoddart, Katie Collier & Huiling Ni

This article was updated in March 2019 to reflect the renaming of NatureWatch NZ to iNaturalist NZ